Process Blog #1: Requiem for Crossbones

5th May 2018 –

I have spent the past few days agonising about nursery rhymes and children’s songs: an element that will feature in Requiem for Crossbones. When I create a new work, I feel it is important to lead with my gut instinct, which usually decides what I feel will work in a location within a few hours of visiting. But it is also important to me that my work is aesthetically in-keeping with, and sensitive towards, a specific location. This includes being historically accurate (to the finest detail) where possible, and can sometimes get in the way of the actual act of composing itself. Over the past few days, for example, my research has encompassed an in-depth investigation into nursery rhymes and children’s songs that may have been known to children living in Southwark from 1800-1850. I sometimes wonder if the length I go to during the research process is an elaborate form of procrastination. But I view the research as a sign of respect, particularly when a piece is situated in an important historical site. I also find it helps to crystallise an idea so I can move forward when the time is right. There are things we don’t know about the people buried at Crossbones. These can only be imagined in the work. But where possible, I want to represent what we do know in what will hopefully be a symbiotic relationship between reality, concept and aesthetic. I want to do this in a subtle way, in layers and fragments; some of which will be subtle enough to go undetected (suggestions of theories regarding what might have been but cannot be known), while others are more obvious. This feels authentic to me. I want to do my best without my ego getting in the way.

In 1992, MOLA undertook an archaeological dig at Crossbones. A majority of the bodies found -which represented as little as 1% of the bodies buried at Crossbones- were babies and children buried between 1800-1850. At the time, there was a cholera epidemic, and the spread of disease in what was a poverty-stricken area, resulted in many deaths of many children and babies. Today I tried to source songs that the children and babies buried at Crossbones might have known or heard from their mother. This hunt for songs was also informed by the knowledge that there were two children’s schools adjacent to Crossbones: the Boys Charity School (est. 1791) and St Saviour’s National Free School for Girls (est. 1819). It is likely that the children who attended these schools lived nearby, and played in the school grounds and surrounding area. The sound of children playing would have been part of the soundscape of Crossbones, if only in part, and I want to represent this.

Illustration from Walter Crane’s A Baby’s Bouquet (c. 1877)

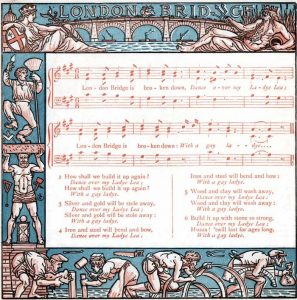

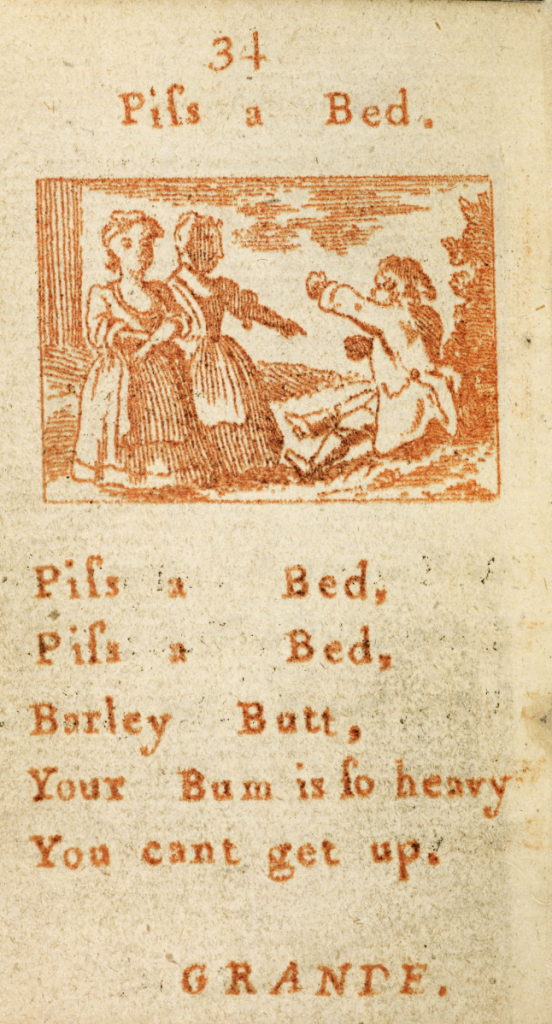

I researched a variety of sources including the British Library children’s book archive on Flickr, and the Roud song indexes, which list folk song collections (including nursery rhymes) from the late 1800s, and song entries in books that date considerably earlier. These songs were often taught orally and later, collected and published in songbooks. This has led me on a wild-goose chase of sorts. For example, one song that I’d like to use is London Bridge Is Falling Down, a song that was in existence at the time, and likely to have been known by local children. However, it’s unbelievable how many incarnations of London Bridge there are. The lyrics and melody differ according to where in London the folk song was collected, and the date it was collected, with even greater variations across the UK. London Bridge as we know it today is entirely different to how it would have been sung then, and it is important to me to use the version that is most likely to have existed in Southwark between 1800 and 1850. Thankfully, I’ve managed to source what I believe to be as authentic a version as there could be for this time period and location (not the version illustrated above!). I have also researched some of the oldest children’s nursery rhyme books found in the United Kingdom, including Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song Book (Nurse Lovechild, 1744). In it, I found this gem:

Lyrics: Piss a Bed, Piss a Bed, Barley Butt, Your bum is so heavy, You can’t get up.

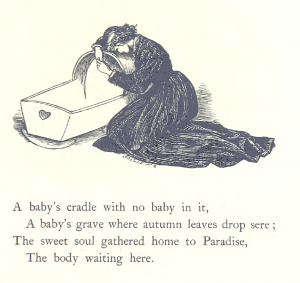

This song has since disappeared from common knowledge, and I can’t imagine it being taught in schools today! It’s impossible to know if the children who lived near Crossbones (and may have even been buried there) might have known it, but I do know that various editions of this songbook were published, including one in 1815 titled Tommy Thumbs Song Book. It’s naughty lyric also makes it a likely candidate to have been shared amongst cheeky school children. Another interesting source from the British Library website was this little song and illustration, about losing a child.

From Sing-Song Nursery Rhyme Book by Christina G. Rossetti (1893, London: Macmillan and Co)

While this book dates later than Crossbones’ existence, it, and many others, frequently depict songs and rhymes featuring deceased children and babies. This can likely be attributed to historical events and the wider social, economical and political circumstances at the time in which these books were written. It is incredibly sad, and not something we are familiar with in children’s books today. I wonder if this is because child-death is not as commonplace as it once was, and is something we often avoid talking about. We can’t really cope with the reality of it, can we?

Tomorrow I shall be working on one of the primary lyrics I will set my music to. It will likely take the form of a 19th century nursery rhyme, where sleep and death seem to be used interchangeably. It’s a difficult subject to comprehend and write about, and I am grateful for my friend. She has very sadly experienced such loss, and is working with me to realise the (unusual) lyrical idea I have. With her permission, I may mention her next time.

Leave a Reply